Composers who want to write for accordion are often not yet familiar with all the possibilities of the instrument, its limitations and notation. In addition to the already existing literature on notation, I try to give composers some guidance and guidelines with explanations, music excerpts, note examples and videos.

In addition to the technical possibilities and limitations, I also tried to put all of this into a musical context. The technical examples are based on existing works, because I think a musical context can be helpful to experience and hear the musical result.

I prefer to work from an aural/musical starting point. With a clear picture of what the composer wants to hear, or what he wants to express, we can figure out how to translate your ideas through the instrument. This invites both performer and composer to be creative and open to new insights, sounds and techniques.

© Erica Roozendaal

The accordion falls under the aerophones, along with the harmonica and harmonium, among others. The word accordion was first used in 1829 by Demian. The name is derived from Akkord: musical chord.

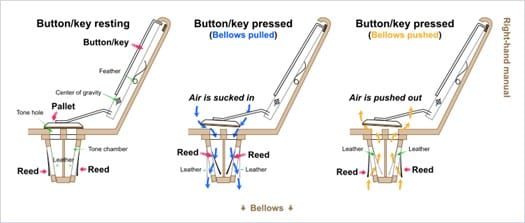

The sound is produced by a so-called free reed: by opening the bellows and pressing buttons air to flows through the reeds. The tone quality of a single tone cannot be changed during playing, but we can control dynamics with the bellows and articulation with the keys.

The classical accordion was developed around the early 1950s. It is also know by the names free-bass accordion, bajan and modern concert accordion. The main difference between a classical accordion and the more familiar traditional accordion is the mechanics of the left hand.

The classical accordion has the ability to switch from the familiar “oom-pah pah” predetermined chord system in the left hand to a single-tone manual keyboard – creating a mirror image of the right hand

Another notable difference is the sound of the doubled 8-foot register (the chapter on registers provides detailed information). Instead of creating a tremolo caused by interference caused by 2 reeds with slightly different tuning, the classical accordion creates sound by combining two choruses with different sound quality, rather than different tuning.

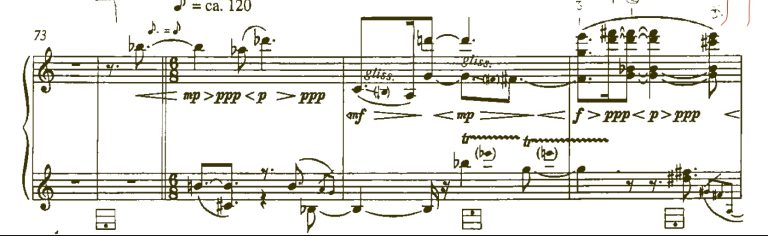

When writing for two hands, the left hand is placed on the lower stave and the right hand on the upper stave. Cross notation is not convenient because our left and right sides are two different parts of the instrument. So whether you place notes on the lower or upper stave is based on which hand plays the notes and not the pitch. Accordion players are familiar with treble and bass clef.

The accordion itself has little resonance. A change in timbre can be created by registers (see below). Because the accordion is an instrument with free reeds we share many characteristics with wind instruments.

The lower the tone, the bigger the tongue. Therefore, low notes need more air, resulting in a more dominant sound when you play an interval. This is something to keep in mind when writing wide intervals.

You could think of the bellows as the “soul” of the instrument: by opening or closing the bellows, air passes through one or more reeds and makes the instrument sound. Because there is only one bellow, we cannot play two lines with two hands and different dynamics.

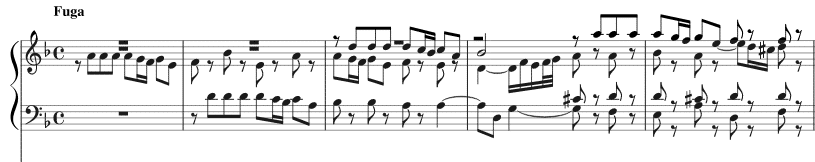

Therefore, the dynamics are mostly written in between the two staves. We can compensate and differentiate dynamics by articulation, registration or dividing tones into different hands. For example, you can emphasize the bottom line in this fugue by Bach through articulation:

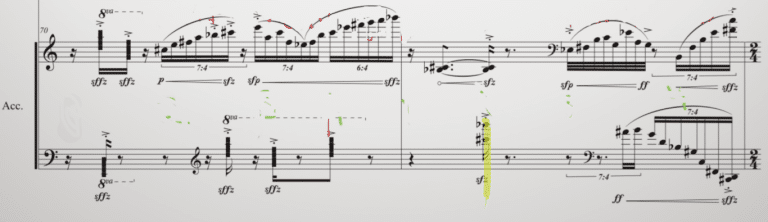

Here is an example of incorrect notation of dynamics: playing a sforzando in the left hand while the right hand has a crescendo is impossible:

The left hand operates the bellows and is responsible for dynamics. You can start a tone al niente, or with an attack, or something in between:

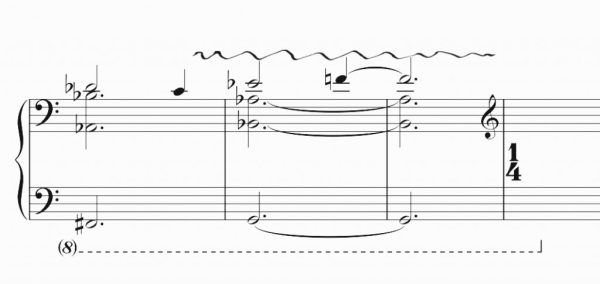

Bellow vibrato The accordionist can play a vibrato in several ways. It can be done with the left hand, right hand, the palm of the hand, by vibrating your hand, by pushing against the instrument, by vibrating your legs, or moving the accordion in other ways. I prefer a clear visual notation of the vibrato sound. With a clear visual notation of how you want the vibrato to sound, the player can work out for himself how to get that done.

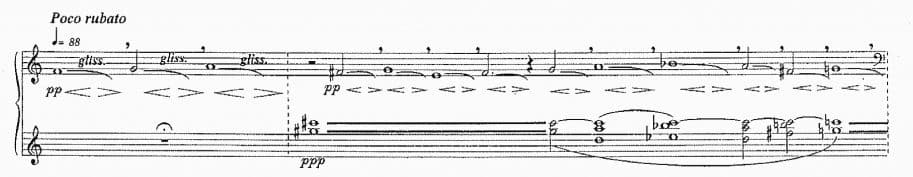

To the right are three examples of different vibrati. Samandari worked with a visual notation of the vibrato, making the direction and speed visually clear.

Martin chose to use an extra stave in front of the bellows to note the rhythm of the vibrato.

Sørensen chose to write “sempre vibrato,” to indicate a constant line running throughout the movement.

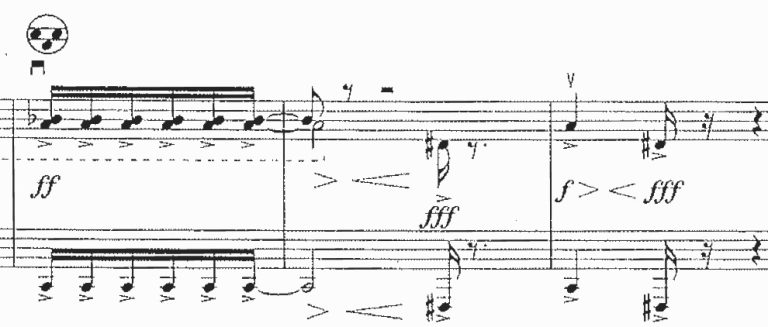

Another commonly used bellows technique is the bellowshake. It is somewhat similar to a tremolo for strings. The bellowshake can be notated in several ways: By using the п and v symbols (п meaning open and v meaning close), or by simply BS (“bellowshake”) and NB (Normal Bellow) writing.

Sometimes rhythmical notation is used, such as when you want to indicate the rhythm of the bellow shake.

The dynamic range when playing a bellowshake is smaller than with a normal bellows, but it is possible to create crescendos, accents, and so on.

Bellowshake in three or four is also possible, using only one corner of the bellows to create a break in the airflow. This is called a ricochet.

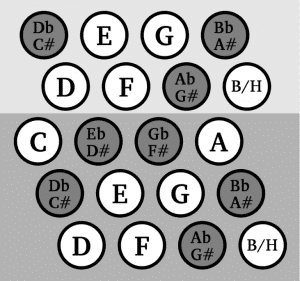

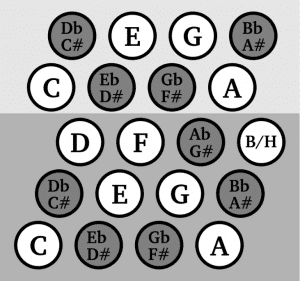

There are many different keyboard systems that all have their own strengths and weaknesses. I play the chromatic button accordion with a converter system. The converter allows me to switch from standard bass to melody bass. The converter and c-griff is now considered standard within classical music, along with the classical accordion with a piano key in the right hand with much the same range.

I play on a Pigini Sirius Bayan c-griff, with buttons on both sides. On this instrument, the left and right hands have the same range. The photo on the left shows the exact range and the instrument itself. The range varies slightly by model.

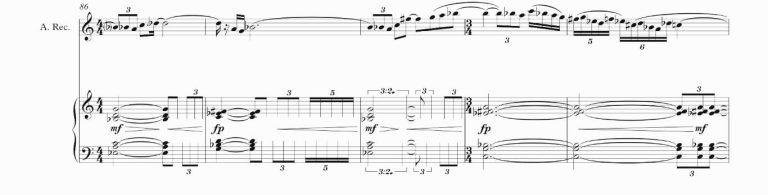

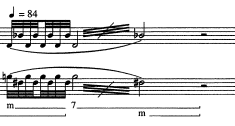

The right side shows an illustration of the two common systems of the right hand. The three rows below are in chromatic order. The two first rows are copied to row four and five, in order to create more fingering options. I play the c-griff system, where the c is on the first row and the chromatic movement is from top to bottom. Because the keys are close together, I can reach two octaves plus a fifth in one hand. A wide range, for example, makes it possible to play the following motif legato:

The left system has two systems:

– the free-bass (or melody bass) system

– the standard bass or stradella bass system

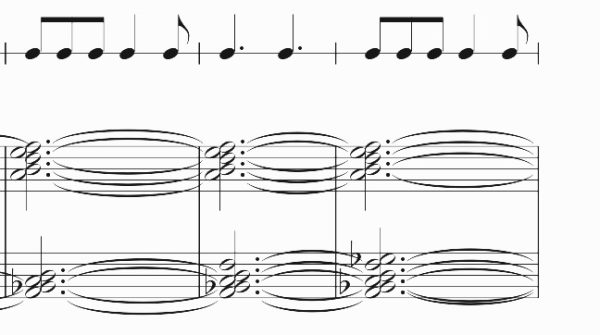

On the melody bass, there is 1 button for 1 tone. On standard bass, you can play an entire chord with 1 knob.

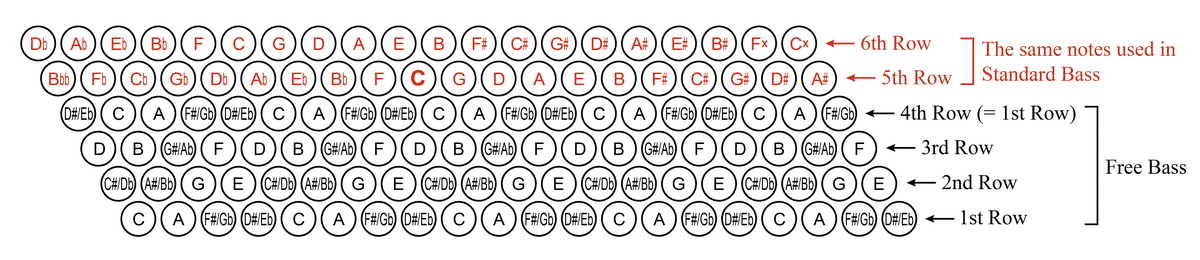

The melody bass system has the same system as the right hand, but mirrored. So you can play melodies.

The notation for stradella bass is different from standard notation. This is necessary because not all instruments have the same chord positions – even though they are always fixed. One always writes the single notes as a note below C3, and the chord notes are written above it.

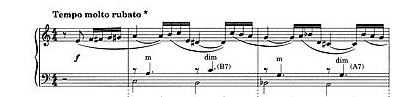

To the right, see three examples of standard bass: Crabb’s arrangement of Piazzola, Berio’s Sequenza and Sanchez-Verdú to get an idea of three different ways to use SB.

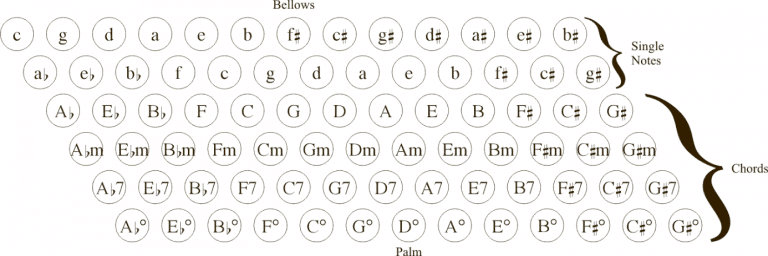

The stradella bass system is the original left-handed system of our instrument. It is based on Western harmony. There are two rows of low single notes and four rows of chords. Above the three sound clips is a picture of the layout.

The left melody bass system has the same system as the right hand, but in mirror image. Today, switching from standard bass to melody bass is done by an internal mechanical switch. The buttons remain the same, but the notes change. So you cannot play chord basses and melody basses at the same time.

However, the fundamental tones of the standard bass system always remain accessible. This makes it possible to combine high notes with a tone from the lowest octave in one hand, as they are available on the 5th and 6th rows.

Technically, the left hand is slightly less flexible than the right hand, because we also operate the bellows with the left hand and we have limited application of the thumb on the left.

Although the range in left and right hands is similar, the purpose of the left hand was originally lower accompaniment and it is still developed with this in mind. Low notes in the left hand speak more easily compared to the right hand and high notes vice versa in the right hand.

You can make choices, depending on the sound quality of the music, as to which hand plays what.

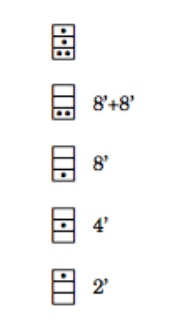

In the right hand, an accordion generally has four different tongue blocks, similar to the different stops on an organ.

All four tongue blocks have different sounds. They can be used separately or combined with any of the other blocks, in other words, you can combine a 16-foot with an 8-foot, for example.

The left hand has three blocks. Two blocks are always an 8′ and a 2′, and depending on the instrument, the third block is a 4′ or an additional 8′.

In the left hand, combination possibilities are more limited. Not all blocks can be played alone, which is why we only have four stops. My instrument has 8′, 8’+8′, 2′ and 8’+8´+2′.

Sound The sound of the instrument differs in both hands, so the 8′ in the left hand is different from the 8′ in the right hand. The tongues of the left hand are literally larger and the left hand is more suited to the low octaves – taking into account, of course, what the music intends.

Because of the construction of the instrument, the sound of the right hand comes more directly to the listener. The lowest octave takes time to catch on, which is a lesser problem with the left hand.

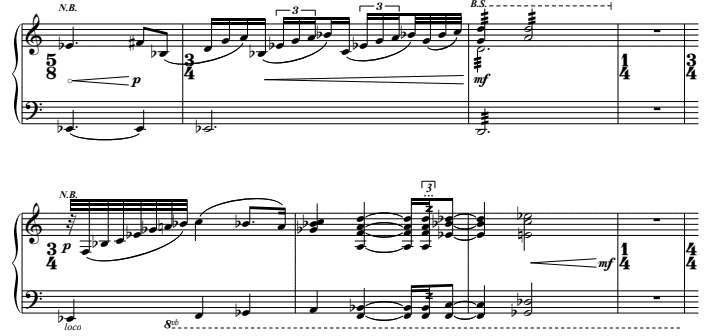

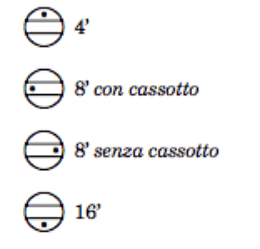

Notation In the right hand, one uses a circle with three chambers to record the registration. In the left hand, a rectangle is preferred.

Noting stops is not a must and can be left to the choice of the performer. Keep in mind that the sound and contrast of stops varies from instrument to instrument.

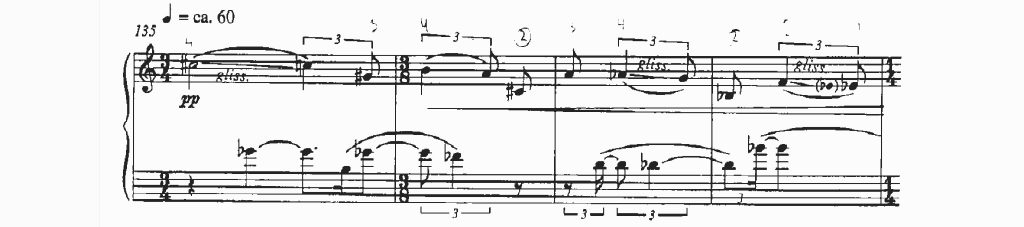

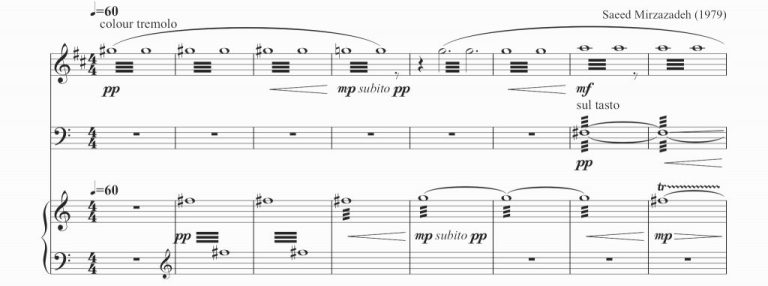

However, some composers make very specific use of registers in which the change itself is part of the music. See the examples to the right.

Pitch bending

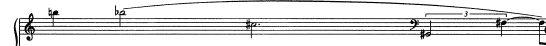

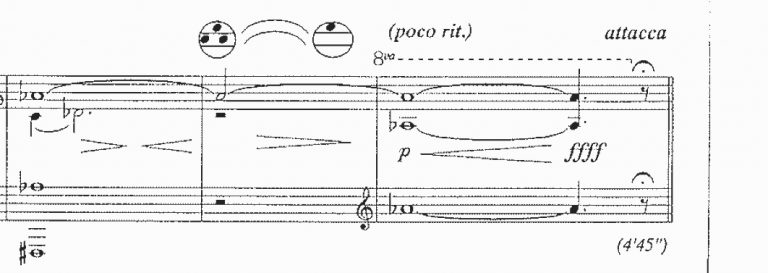

This is also known as tone glissandi and is created by applying pressure to the bellows and very gently pressing a button halfway down. The way this works is by limiting the air supply so that the reed cannot reach its natural rate of vibration. You can control the bending with the bellows – more pressure means greater bending.

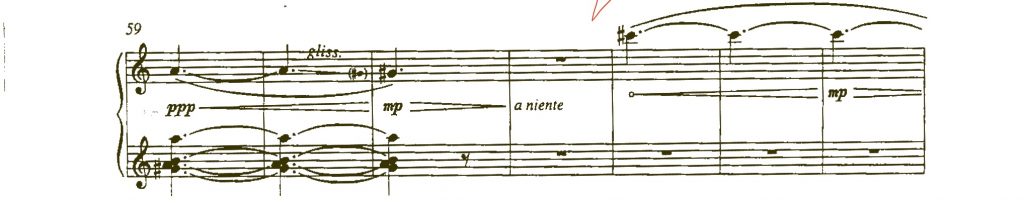

The tone can only go down. It is possible to start at the lower pitch, but that requires some preparation. Tone glissandi work best in the right hand. Lower notes bend more easily and are easier to control – the lowest octave can often bend a minor third. Above d’, bending becomes a challenge and I rarely get above a quarter note.

A pure pitch-bend can only be created by a register with one tongue. Using combinations of tongues results in hearing less of a bow and hearing more of a false tone, because all tongues respond differently. Furthermore, using a caseload register generally works better.

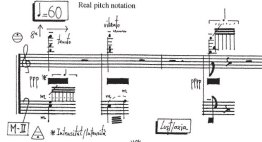

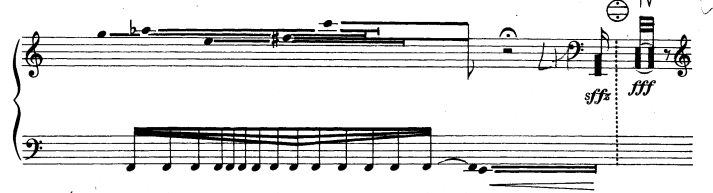

In Looking on Darkness, the pitch of the end of the note is indicated, as is the question of whether the end should not be played on an actual lower key or held as a bow of the key above it.

In Black Birds, the only information is the glissando itself. The inflection itself is more important – the final pitch is not fixed.

Button glissandi

There are two different button glissandi. It can be made by sliding on one note at a time or on an entire cluster. Only a piano keyboard can make a glissando over white keys. On a button keyboard, a vertical glissando results in a glisando with minor thirds.

Clusters can be made with the palm of the hand, a fist, the forearm or a few fingers. If a specific technique is needed, it is noted by simply writing what to use.

A cluster is noted by black filled note values within the lowest and highest note values.

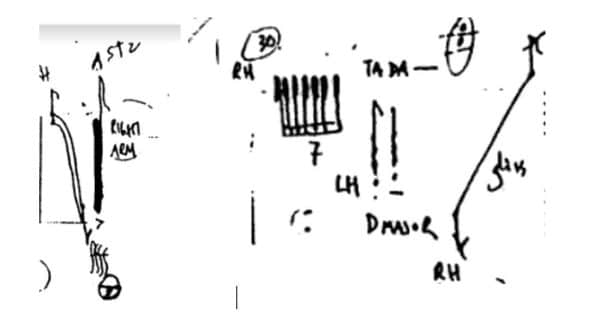

For both techniques, a clear visual image of the desired sound result is optimal:

Percussive sounds

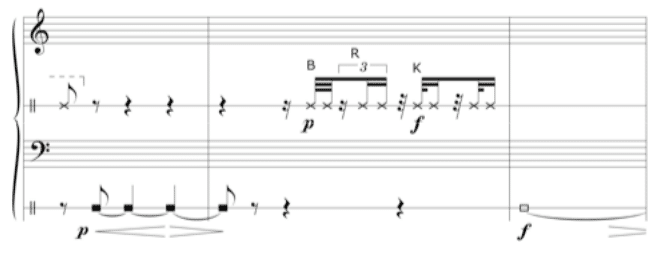

There are several types of percussion sounds that are commonly used: air knob, button sound, striking the bellows and clicking register changes. In all cases, it is wise to write a performing note, even if the notation is common.

The Manual of Accordion Notation suggests capital letters to indicate which pitch sound to use: K (Keyboard), B (Bellows), R (Register). See the example below. The sounds are often notated with an “x” as the note head, a notation also used in other instruments. The ‘x’ can also be circled so that the length of the note can be noted precisely.

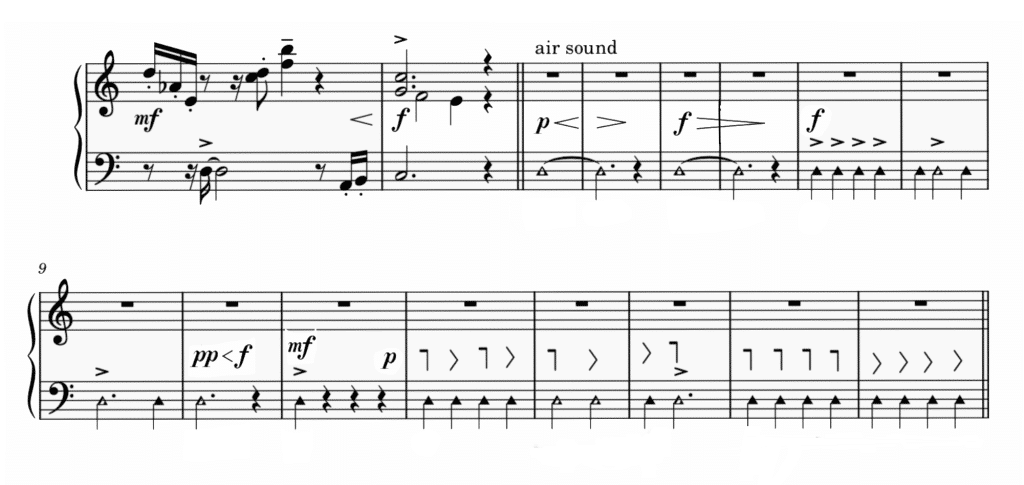

Air noise

The left hand has an air button, which can be used for both musical and practical purposes. You can treat it like a note, in the sense that you can make dynamics, use bellowshake, and so on, with the air sound.

Since the air sound is played by the left hand, it may be practical to note the air sounds in the left hand and other toneless sounds in the right hand. Another option is to use the space between the two staves, or an additional stave.

Specific bellows directions can be noted while using the air knob, but this is not necessary because it only has a visual effect, it does not affect the “air sound.

All recordings were made by me unless otherwise indicated.

I am grateful for colleagues who have done similar work.

Useful information for follow-up study is the Handbook of Accordion Notation, written by Geir Draugsvoll and Erik Hoeysgaard, translated and edited by James Crabb.

Would you like to write an accordion piece for me? If so, please be sure to contact me!

Would you like to write for accordion, cello and/or clarinet, and are interested in learning more? Maybe the Roadrunner Academy is for you.